How Australia Became a Death-Avoidant Culture: The Consequences of Cultural and Institutional Choices

An exploration of how Australia’s cultural, historical, and institutional shifts have created a death-avoidant society - and what it will take to change it.

8/15/20256 min read

How Australia Became a Death-Avoidant Culture

Written by: Samantha Waite of Taboo Education

In contemporary Australia, open discussions about death remain rare and often uncomfortable. While the country performs better than some, such as the United States, it still lags behind others like Ireland when it comes to fostering healthy, open attitudes about mortality. Avoidance of death- socially, emotionally, and institutionally- is not an ingrained cultural feature, but a relatively recent development. This makes it possible, and even promising, to reimagine our collective approach, provided we first understand how we arrived at this point.

What Does Death Avoidance Look Like Today?

Death avoidance in Australia operates across both personal and systemic levels. While individuals may insist they are not afraid of death, cultural patterns suggest otherwise. Many Australians avoid making end-of-life plans, such as drafting a will or completing an advance care directive. Parents often sidestep conversations about death with their children, fearing these talks may cause unnecessary distress. People delay medical appointments due to anxiety about serious diagnoses. Conversations about ageing, dying, or care preferences in later life are often postponed indefinitely, if they happen at all.

Within healthcare, avoidance shows up in the way we manage the end of life. Most people die in hospitals rather than at home, often surrounded by machines instead of loved ones. Medical training focuses on cure and prolongation of life, not on the process of dying or supporting families through grief. In social settings, individuals experiencing loss frequently report feeling isolated or abandoned. Even funerals, once spaces for shared mourning, have increasingly shifted toward “celebrations of life,” which may minimise or obscure the emotional realities of grief.

Although death is a universal part of human experience, very few Australians have seen a dead body or witnessed the process of dying. For something so common and inevitable, this absence of exposure creates a profound discomfort and unfamiliarity that reinforces our cultural silence.

What Death Looked Like Before the Shift

Historically, Australians had a far more intimate and community-centred relationship with death. Dying often occurred in the home, surrounded by family members who took on both emotional and practical roles. It was not unusual for children to be present, for neighbours to offer support, and for the deceased to remain in the home until burial. Families washed and dressed the body, built the coffin, and held the wake in their living rooms or local halls. Grief was expressed openly, with rituals that were embodied, local, and deeply connected to both land and kin. Death was seen as a part of life, not as a medical or logistical problem to be managed by professionals.

Today, death is largely managed by institutions. Most people die in hospitals, cared for by medical staff instead of family. Funeral directors now handle tasks once carried out at home, and grief is expected to be quiet and brief. This shift was gradual, shaped by war, medicalisation, and the growth of the funeral industry.

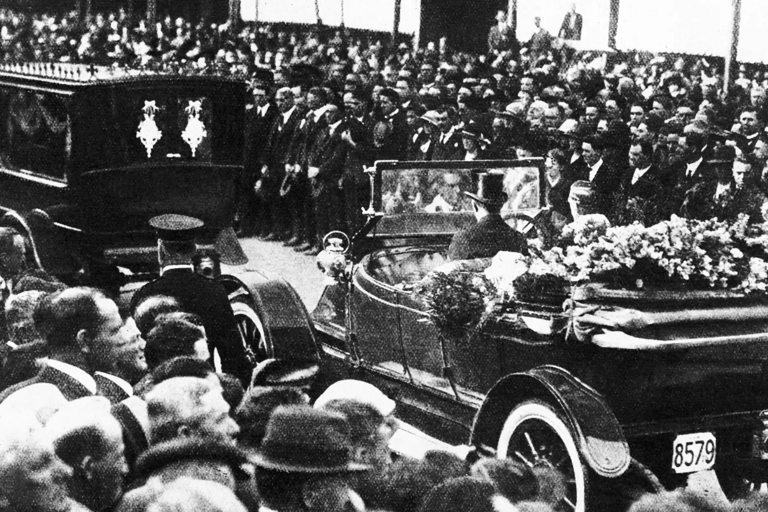

War and the Remaking of Grief

The two World Wars reshaped how Australians experienced death and mourning. Prior to these global conflicts, most people died at home, and grief was open and supported by the local community. War, however, pushed death to distant battlefields. Families received news of deaths without bodies to bury or rituals to complete. The absence of physical remains meant a reliance on memorials, plaques, and public ceremonies in place of private mourning.

Grief was reframed as a national, symbolic act. The rituals of remembrance became formal and collective, often managed by government or military institutions. In the process, personal grief was subdued. Emotional restraint became a sign of dignity. Loud or messy grief was discouraged. Over time, this style of grieving permeated civilian life, encouraging silence and stoicism in the face of loss.

War also introduced the idea that death should be meaningful. Deaths on the battlefield were often described using language of sacrifice, honour, and national pride. In contrast, deaths from illness or ageing began to feel less justifiable. This set the stage for a cultural mindset in which death without purpose seemed like a failure, rather than a natural conclusion to life.

The Medicalisation of Dying

As Colonel Potter famously said in the television series MASH*, “War advances bring medical advances.” Developments in medical science in the decades following the wars moved death from the home to the hospital. The emergence of antibiotics, surgery, life-support technology, and intensive care shifted the focus of healthcare toward the preservation and extension of life. As a result, dying became framed as a medical problem to be solved, rather than a human experience to be supported.

Patients, often encouraged by families, underwent invasive and aggressive treatments in the hope of a cure, even when the chances were slim. Physicians, trained primarily to heal, were not always prepared to guide patients through dying. Conversations about prognosis, comfort care, or quality of life were frequently postponed or avoided altogether.

This shift also changed the emotional terrain. Dying became an isolated experience behind hospital curtains, where children were rarely present and families were often unprepared. The body, once cared for by loved ones, was now managed by strangers. Grief became a private burden, rather than a shared process.

Medicalisation deepened the belief that death was something to be resisted at all costs. A death that could not be prevented came to be seen as a failure—of the patient, the family, or the healthcare system. This has left many clinicians reluctant to acknowledge when death is approaching, and many families unprepared when it arrives.

The Rise of the Funeral Industry

Alongside the expansion of hospitals, the funeral industry grew rapidly. Where families and communities had once been responsible for preparing the dead, these tasks were now outsourced to professionals. Funeral directors offered services that were efficient, discreet, and emotionally contained.

This shift brought convenience, but it also created distance. The tasks of washing the body, building the coffin, or digging the grave were once acts of care and farewell. Their removal from the home eroded the personal engagement many once had with death. Funerals became increasingly standardised, often following a scripted, formalised format that left little room for genuine emotional expression.

The industry also contributed to social norms around grief. Polished services with tasteful speeches became the benchmark for what was considered “appropriate” grief. Loud mourning or overt displays of sorrow were discouraged. As a result, Australians lost many of the communal, expressive ways they once processed loss.

Why This History Matters

Understanding how we became a death-avoidant culture helps explain many challenges in our healthcare system and our private lives. It clarifies why families often feel lost during end-of-life care, why doctors may hesitate to raise the topic of dying, and why individuals are left without a language for grief.

This history also reminds us that death avoidance is not inevitable. It is the product of social, political, and institutional decisions. The wars encouraged distance in grief. Medicine taught us to see death as a problem. The funeral industry taught us to step aside.

But there are alternatives. We can bring death back into ordinary life- in homes, in education, and in community spaces. We can restore old rituals or create new ones. We can foster environments where people are allowed to talk about death without shame and mourn in ways that feel authentic.

Becoming more comfortable with death is not about embracing despair. It is about reducing fear, building trust, and creating cultures of care. It is about meeting the end of life with presence and dignity, just as we do with birth, marriage, and other significant transitions.

Moving Forward

Australia is not unique in its discomfort with death. Many modern nations have followed similar paths, shaped by war, science, and capitalism. Yet because this shift occurred relatively recently, it is possible to change course.

Reclaiming a healthier relationship with death will take effort across multiple sectors, including education, medicine, public health, and community leadership. But it can be done. Individuals, families, and professionals can all contribute to a cultural reset that makes space for dying, grieving, and remembering.

The work begins by talking about death more openly. It continues with action—writing wills, having honest conversations, creating supportive spaces for grief. And it ends, ideally, with a society that no longer avoids death, but meets it with clarity, compassion, and care.