Executioners in History: The Stigma, Power, and Strange Honour

How were executioners treated throughout history This blog explores the changing roles, status, and stigma of executioners from ancient civilisations to the modern era.

12/18/20255 min read

How Were Executioners Treated Throughout History?

Execution has been part of most legal systems across human history. For much of our past, death was considered an appropriate response to crime, betrayal, or perceived moral failure. But while societies debated who deserved to die, far less attention was given to a quieter question:

What did we think of the person who carried out the sentence?

Executioners occupied one of the most contradictory roles in human history. They were essential to systems of law, order, and power — yet often feared, hidden, shunned, or erased. To understand how executioners were treated is to understand how societies have grappled with death, punishment, responsibility, and moral distance.

The Invisible Executioners of the Ancient World

In ancient Mesopotamia, some of the earliest written laws — including the Code of Hammurabi — prescribed numerous death penalties. Yet surviving records rarely mention the individuals who carried them out. Executioners were typically slaves or low-ranking soldiers, deliberately unnamed and undocumented.

This silence was not accidental. By erasing executioners from the record, responsibility was placed squarely on rulers and judges, not on the human hands that enacted death. Invisibility itself became a form of stigma — executioners were used, but denied identity.

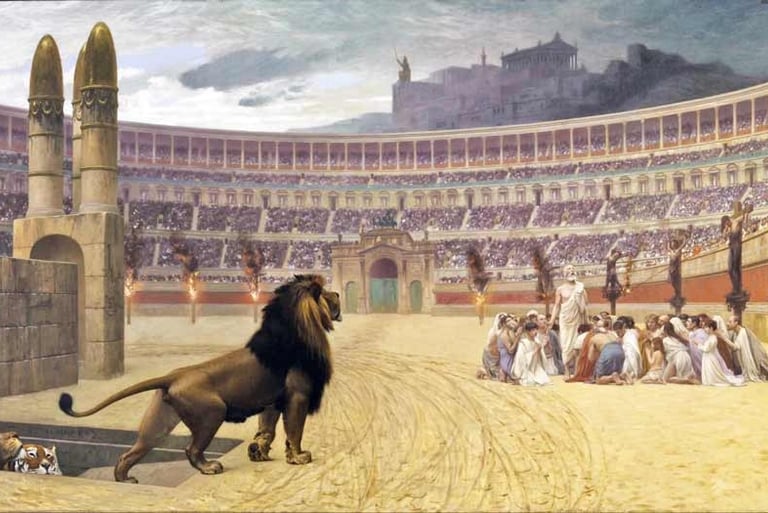

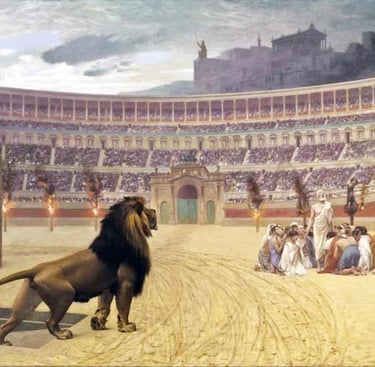

Ancient Rome took a different approach. Executions were public, theatrical, and often brutal. Amphitheatres, crucifixions, and spectacles of punishment drew crowds. And yet, even here, the people responsible for carrying out executions were diminished. Slaves released wild animals or finished off condemned bodies. Gladiators might become famous, but executioners remained nameless.

Rome made death visible — but kept the executioner morally distant.

When Killing Was Communal, Not Shameful

Not all societies treated executioners as outsiders.

In early medieval Scandinavia, before Christianisation, executions were tied to honour and kinship. Punishment was often carried out by families or communities, not professionals. The person delivering the fatal blow was not a pariah, but a representative of communal justice or injured kin.

As Christianity spread and law became centralised, professional executioners emerged — and with them came stigma. What was once an act of honour became a career marked by disgrace. This shift reveals something important: stigma often followed bureaucratisation, not violence itself.

A similar pattern existed in pre-colonial Indigenous Australia. Within payback systems, death sentences were carried out by kin groups or designated warriors. These acts were embedded within spiritual and social frameworks, not delegated to isolated individuals. There was no executioner caste, and no inherited shame. Justice remained relational, not detached.

Sacred Violence and Ritual Power

In some cultures, execution was not punishment at all — it was sacred duty.

In the Aztec Empire, sacrifice and execution were essential to cosmic balance. Priests and warriors carried out killings as offerings to the gods, believed necessary to sustain the universe itself. Executioners were visible, respected, and powerful — though also feared for their proximity to blood and divinity.

The Ashanti Empire of West Africa also linked execution to authority and ritual. Executioners acted as agents of the king and could be honoured warriors or trusted officials. Their role carried spiritual risk, but not disgrace. Where kingship was sacred, executioners could be elevated rather than excluded.

Europe’s Outcasts: Hereditary Stigma and Social Exile

Europe developed some of the most extreme forms of executioner stigma.

In medieval England, executioners were often criminals forced into the role. They lived on the edges of towns, barred from taverns and guilds, socially untouchable. Payment sometimes came in the form of the condemned’s clothing — a symbol of both reward and contamination.

Renaissance Italy and France went further, creating hereditary executioner families. Dynasties like the Sansons became infamous, their children inheriting exclusion regardless of personal choice. Marriage between executioner families reinforced a caste-like system that was difficult to escape.

Prussia presents a striking contradiction. Executioners were granted exclusive rights to certain trades, such as hide dealing, giving them financial security. Yet social stigma remained intact. They could be wealthy — and still deeply reviled.

Japan under the Tokugawa era institutionalised stigma most rigidly. Executioners were part of the eta (later burakumin) caste, permanently excluded from mainstream society. Their association with death denied them full humanity, a legacy that persisted long after legal abolition.

Secrecy, State Power, and the Disappearing Executioner

Authoritarian systems often erased executioners in different ways.

In the Ottoman Empire, executioners were palace servants, frequently slaves, who carried out sentences in private — often by strangulation with silk cords. Their anonymity reinforced the mystique of absolute rule. Even in death, executioners were erased, buried in unmarked graves.

Mughal India integrated executioners into court life. While some punishments were spectacular, executioners did not form a hereditary caste. Their identities mattered less than the emperor’s will.

In the Mongol Empire, soldiers themselves often carried out executions. Violence was collective and normalised within military structures. Without a professional executioner, stigma dissolved into shared responsibility.

Public Theatre and Private Shame

Colonial America inherited European discomfort with executioners, but inconsistently. Professional executioners were rare. Sheriffs or conscripted criminals often filled the role. In Puritan New England, executioners were paradoxical figures — instruments of divine justice and symbols of sin.

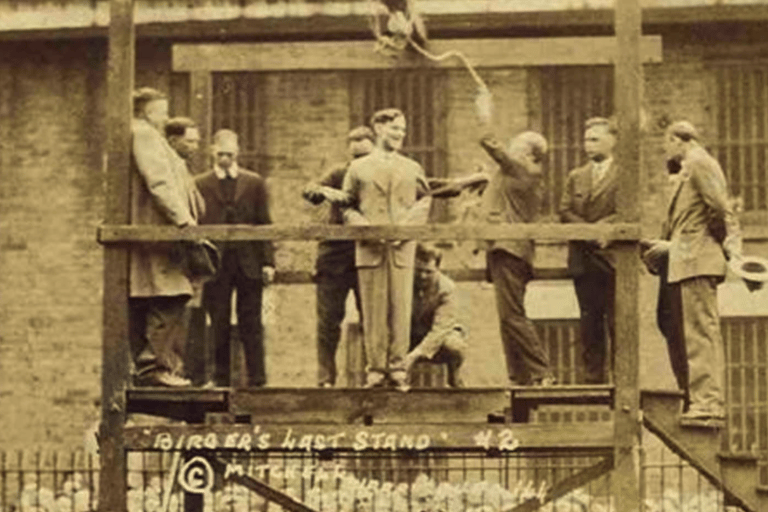

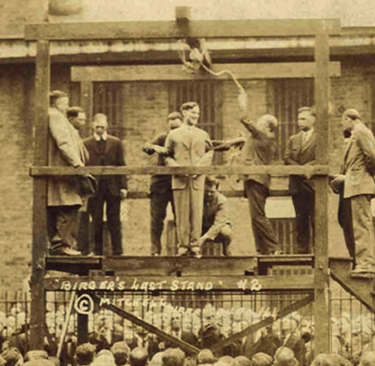

In 19th-century Britain, official hangmen emerged and became minor celebrities. Names like William Calcraft appeared in newspapers, yet fame did not bring respect. Hangmen were often poorly paid, socially isolated, and ridiculed.

The United States reflected a similar tension. Executioners were needed but unwanted. Known, yet never fully integrated. Justice demanded their presence — society rejected their proximity.

The Totalitarian Turn

In 20th-century Germany, the executioner’s identity shifted dramatically under political extremism. Johann Reichhart, a professional executioner, carried out thousands of guillotine executions under the Nazi regime. During the war, he was a loyal state servant. After it, he became a symbol of atrocity.

His defence — that he was “just following the law” — highlights a painful truth: executioners are judged not only by their actions, but by the morality of the state they serve.

What Executioners Reveal About Us

Across cultures and centuries, executioners have been mirrors of societal values.

Where death was sacred, executioners were priests.

Where justice was communal, they were kin.

Where punishment was theatre, they were performers.

Where law was bureaucratic, they were erased.

Executioners were necessary — and yet deeply uncomfortable.

Their treatment tells us less about them, and more about our attempts to distance ourselves from violence. We want punishment without pollution. Order without cruelty. Justice without responsibility.

This history invites a difficult reflection.

In places where the death penalty still exists today — China, Iran, the United States, Saudi Arabia — how are executioners treated by their neighbours? Would we welcome them into our communities? Into our families?

For those who support the death penalty, how close to home are we willing to let it come?

Watch / Explore Further

At Taboo Education, we believe talking about death — honestly and thoughtfully — reveals how we live, how we judge, and how we care.

And with that, go talk death.